Afterimages of Anna May Wong at Potsdamer Platz

Afterimages of Anna May Wong at Potsdamer Platz

This is my love letter to Anna May Wong, the Chinese American actress who lived and worked in Berlin from 1928-1930, and left traces in the city that persist to this day. The rising star first traveled across the Atlantic in search of more artistic freedom, due to limited opportunities for work in 1920s Hollywood — at the time, most offers she received were for supporting roles as a servant or tragic figure. In Germany, she was signed to be the star of three films: SONG (1928), GROSSSTADTSCHMETTERLING (Pavement Butterfly, 1929), and HAI-TANG (1930). While none of these three films granted Wong the happily-ever-after she sought, the less stereotypical leading roles allowed her to demonstrate more of her acting prowess, to dance in spectacular set pieces, and even to showcase her singing, as in HAI-TANG, her first sound film. As an Asian American who studies the history of diasporic Asian film representations and spends plenty of time in Germany, I have thoroughly enjoyed learning more about Wong’s films and experiences in Weimar-era Germany.

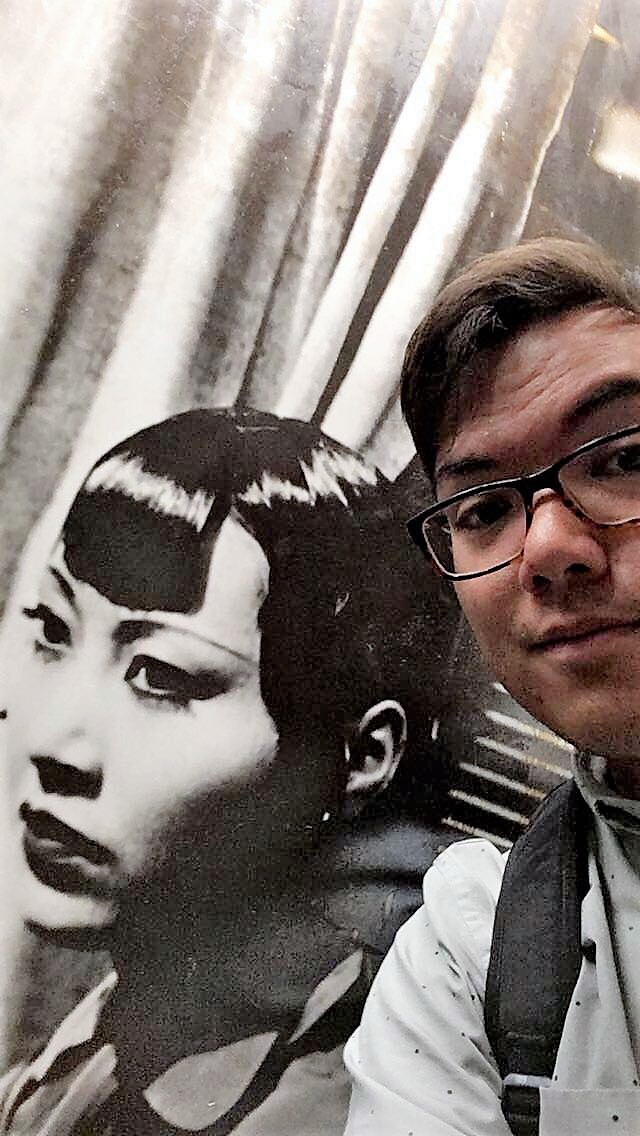

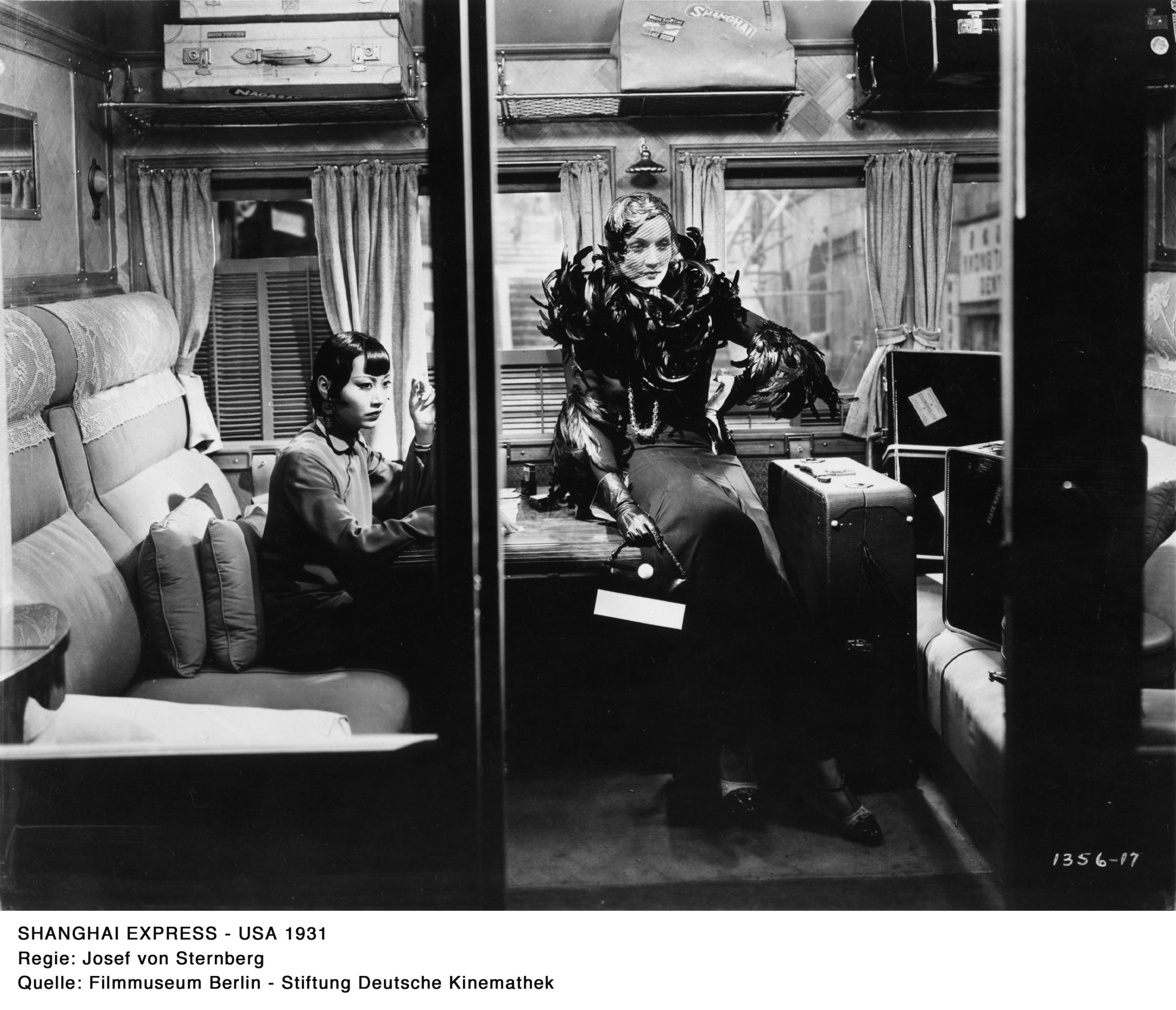

When I visited Berlin in the summers of 2017-2019, I found myself continually encountering traces of Wong at the multi-story “Filmhaus” at Potsdamer Str. 2, which contains a film museum, the libraries and archives of the Deutsche Kinemathek, and the Arsenal arthouse theater. For example, following a 2017 archival viewing for my Asian German film research on the seventh floor of the building, I exited the screening room and proceeded into the hallway to find an impressive photo of Wong on the wall. The image depicted Wong alongside the queer German icon—and Wong’s rumored lover—Marlene Dietrich, taken from the film SHANGHAI EXPRESS (1932). To see Anna May Wong so prominently featured in a German film archive was a delightful surprise. I immediately took a selfie with her; when else, I thought, would I have the chance to see her in Berlin? Little did I know that Wong would continually reappear in the Filmhaus for years to come, like an afterimage lingering close to 90 years later.

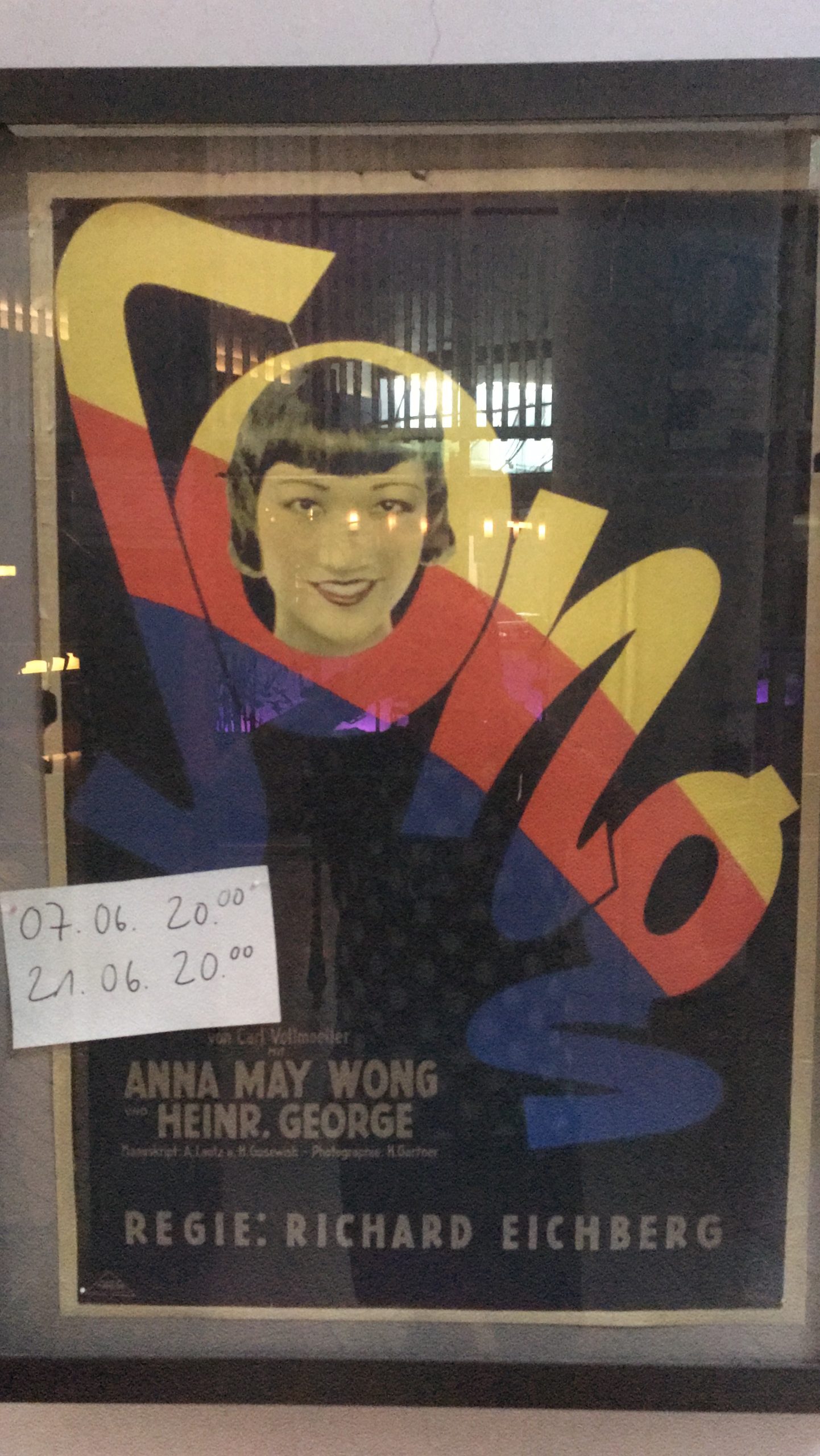

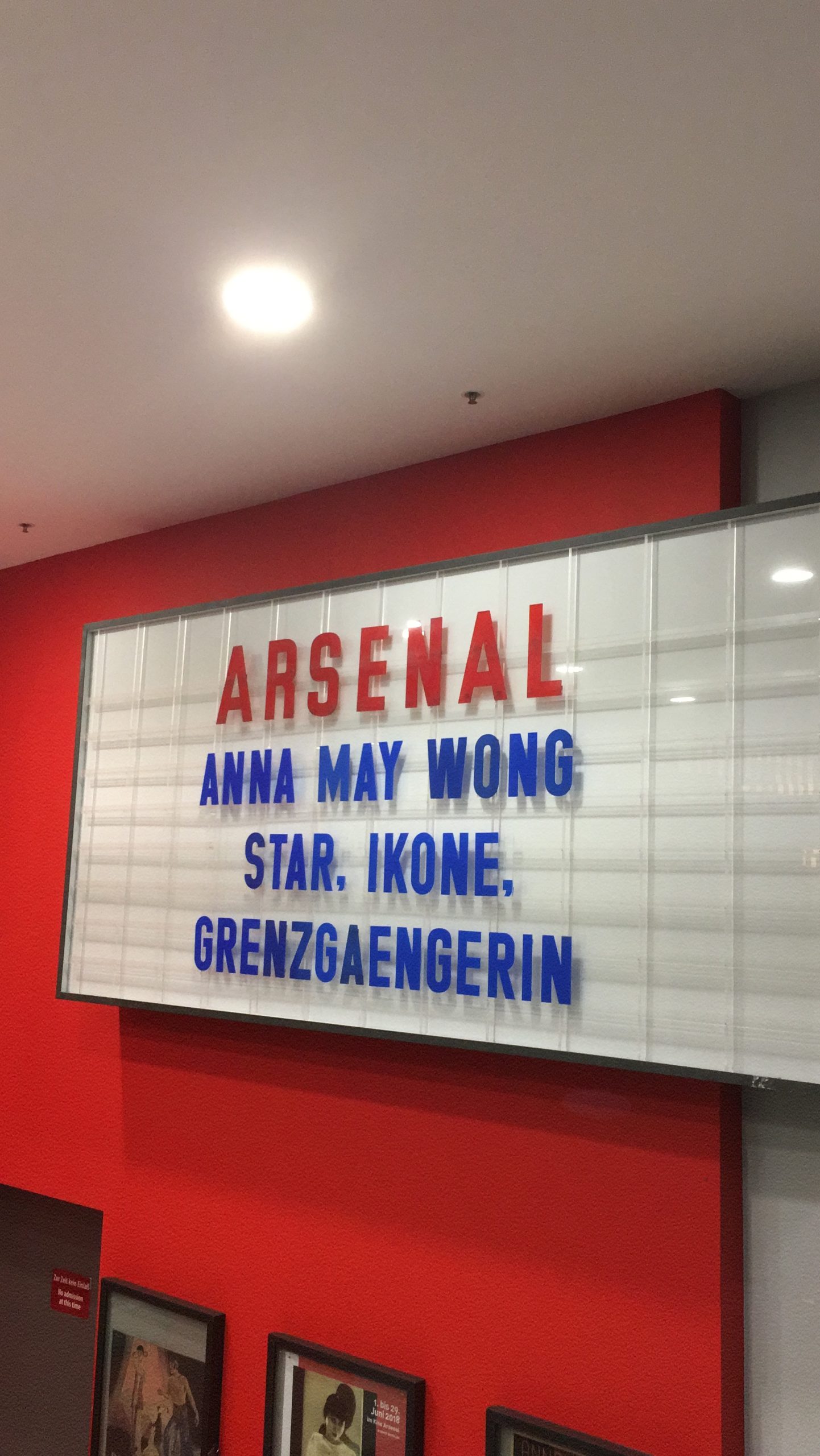

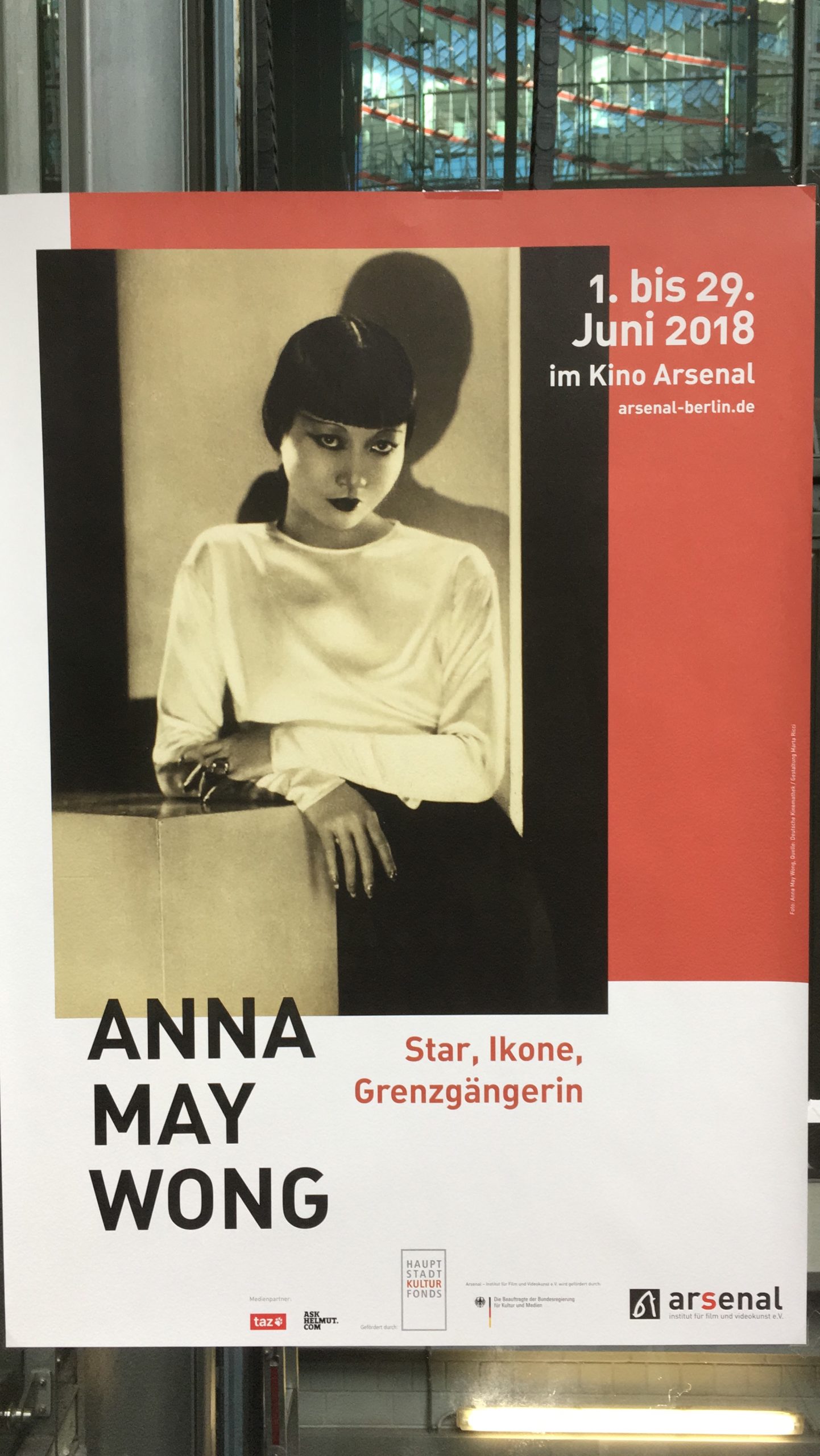

I returned to Berlin in 2018 during a month-long film retrospective dedicated to the actress, entitled ANNA MAY WONG – STAR, IKONE, GRENZGÄNGERIN (Star, Icon, Boundary Breaker). The twelve-film program, which included all three of Wong’s German pictures, took place in Arsenal, the arthouse theater on the basement level of the Filmhaus. Vintage posters advertising her films adorned the wall outside of the Arsenal entrance, inviting us to see that an Asian film star in Germany was possible as early as the 1920s. While watching Wong’s 1929 silent film, I remember being engrossed by the glamorous close-ups of her emotive expressions and her signature bobbed, “flapper” hairstyle. It was uncanny and awe-inspiring to see such an early German film fronted by an East Asian face. I kept the program booklet and a postcard from the event as a keepsake of the cinematic experience.

During my 2019 trip to Berlin, Wong inhabited yet another space in the Filmhaus. On the upper floors of the film museum, she was featured in various parts of the special exhibition KINO DER MODERNE: FILM IN DER WEIMARER REPUBLIK (Modern Cinema – Film in the Weimar Republic). Displayed photos included a snapshot of her signing autographs for German fans in 1928, as well as a newspaper clipping with her portrait and the headline “Chinesische Schönheit: Der Filmstern Anna May Wong” (Chinese Beauty: The Film Star Anna May Wong). A clip montage at the exhibition also presented scenes from Wong’s German filmography. Another particularly striking item at the exhibition was a photo of a custom film marquee from 1929, which decorated the former Universum cinema in Berlin-Charlottenburg, with a larger-than-life cutout of Wong’s face in the center. I took home a postcard of this image that I bought at the museum shop, as well as a copy of the catalog for the whole special exhibition.

Anna May Wong clearly made an impact on German cinema during her two years in Berlin; she certainly made an impact on my visits to the city. She was the earliest East Asian star to grace the German silver screen, and it was empowering to see this celebrated almost a century later. Her time and acting experiences in Europe helped make her the star she would become back in 1930s Hollywood. Hopefully, her legacy will continue to be remembered in Berlin.